This month, I’ve been moving with and like the river.

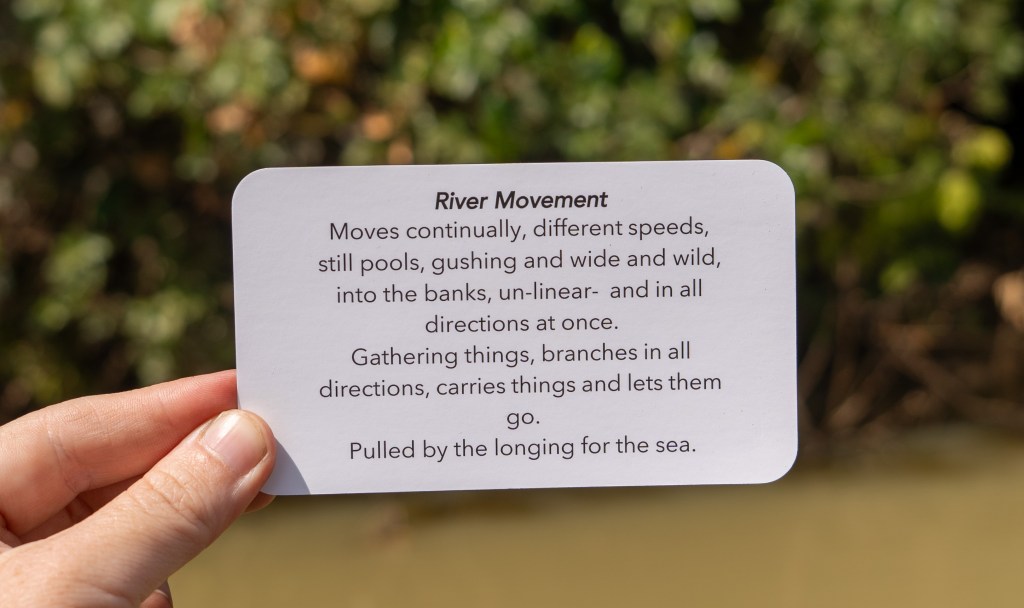

Before leaving the UK, I asked a few people to write me letters I could open when I was finding things particularly rough. One I opened recently, from the radiant Elena, was a card from a set made by dance artist Cai Tomos (which you can buy from Little Red Tarot, the only tarot shop you need). The prompt: river movement.

I took it with me a few days later when I was out on the river participating in the December hippo count. The prompt was apt, an important reminder of the value of going with the movement of the research process rather than trying to be in control (when I went to Ghana for my MSc research, my supervisor only gave me one piece of advice: “let go”). Embracing fluidity, un-linearity, movement at different speeds and in different directions for me means seeing the research process as one of open-ended exploration, with unexpected encounters sometimes being some of the most meaningful.

This kind of approach might not fit with every research methodology, but for me, it feels important to accept that plans and paths change. Some of the things I might be interested in understanding in more detail might not be things people want to talk about or do with me. Some of the things I thought I might be interested in understanding might not actually interest in practice. Instead, it’s about staying with what’s generative, and changing direction or focus when needed. Currents might pull me, and I might go with them, or not.

This is an important lesson for me, and not just regarding the research process. The last six months have been difficult, with an extreme amount of change in my life having destabilised me and taken a serious toll on my mental health. I have OCD, which I generally manage pretty well, but in the latter part of last year I wasn’t coping. At its core, OCD is having a low tolerance for uncertainty – that’s what drives the processes of rumination and checking. Not being in control, or things just being deeply uncertain, is challenging.

In the last week or so I’ve been shifting my research approach into one that’s more improvised, less driven by having a clear set of goals for the data I want to collect, and (I’m sure it’s linked) I’ve also been having a lot of the same intrusive thought, like a mantra my subconscious is beaming up: I don’t know what I’m doing.

It made me feel anxious at first, hearing that thought jiggle around inside my head. But in movement – walking around villages as the sun sets, traversing sandy, rocky tracks on a motorbike, paddling on the river – I started to feel at peace with it. I don’t really know what I’m doing, and that’s also OK, maybe part of the point; I’m navigating, I’m moving in one way and then the other, I’m picking things up and then letting them go.

As I’ve been figuring out how to better care for my OCD-brain, I’ve been reminded of the importance of embodiment, returning to sensory knowledge and experience rather than focussing solely on the cerebral. That curiosity has made embodied knowledge, especially embodied environmental knowledge, an emergent theme in my fieldwork. I think the seeds of this interest might have been sowed in my last month in London before coming to Ghana, when I was temporarily living in dancer Gill Clarke’s house, spending blissful days sitting in her old library, surrounded by her incredible collection of books, many of them on the topic of embodied knowing.

This week I had the immense blessing on spending a few days living with A and his family, Hausa fisherfolk staying on the edge of the protected zone, fairly near the river. I joined them in the evenings, as he and his sons went out on the river to set up fish traps for the next day, and again the next day at dawn, when they returned to empty them, before preparing the fish to take into Wechiau to sell.

At that time on the river in the gloaming and dawn the birdlife is incredible: white cattle egrets float from one side of the river to the other; flocks of whistling ducks move down the river making their distinctive call; brightly coloured bee eaters and sunbirds startle from the bushes along the river banks.

A’s sons paddle the canoe and process the fish afterwards; they’re apprentices to A, learning through doing. They know the river intimately, in ways built on sensory and somatic engagement: how the water feels, the sounds the birds make, the waves indicating hippos’ movements. This kind of knowledge can be de-valued, seen as less valid than knowledge gained through scientific methods. These embodied ways of knowing are, however, built up over time, based on repeat experience; knowledge might be generated which isn’t cognitive, but it’s no less than that which is.

This theme has also come up in some of the music I’ve experienced recently. Multiple people have told me about the songs they sing when farming, giving thanks to the earth and encouraging a good harvest. It’s currently the dry season, so very little farming is happening, and when I ask them if they’ll share one of the songs they realise they can’t. You have to be there, they say; you have to be actually holding a tool, standing in the farm, working, for the sound to come out. The songs don’t exist outside of the movement and activity they accompany.

It comes up also in my attempt to learn to play the gyil, the wooden xylophone found in northern Ghana, Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire. I had a classical music education and while I’m very rusty and wouldn’t consider my musical abilities that strong, I still tend heavily towards wanting to understand something in order to play it. When my teacher plays a new phrase, that same thought comes back: I don’t know what I’m doing. But now I’m deliberately trying to not try and cognitively process it. I’m just trying to hear it, feel it, play it. My teacher emphasises something similar – keep playing it, he says, until it’s fully inside you. I’ve got absolutely no idea how to notate any of these rhythms, but that’s ok, because I can hear them, I can feel them, and I can at least attempt to play them.

Thanks for reading!